Sanctions put squeeze on Mali's lucrative cotton sector

Malian cotton farmers are set to produce a bumper crop this year, but Mahamadou Konate is worried, belying the smile he wears as he paces through his field.

Economic and diplomatic sanctions recently imposed on the poor, conflict-torn Sahel state threaten one of its few economic motors: the cotton sector.

Mali has traditionally been one of Africa's leading cotton producers. During the growing season, the cash crop blankets swathes of the vast country in white. Locals call cotton "white gold".

"If they sanction us, how are we going to sell our cotton abroad?" asks Konate, standing in the middle of one of his fields.

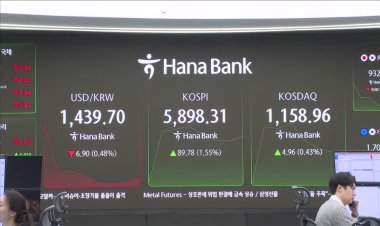

Earlier this month, the West African bloc ECOWAS imposed a trade embargo and shut borders with Mali over delayed elections in the country.

West African leaders also halted financial aid to Mali and froze the country's assets at the Central Bank of West African States.

The move followed a proposal by Mali's junta, which seized power in August 2020, to stay in power for up to five years before staging a vote -- despite international demands that it respect a promise to hold a poll in February.

The sanctions threaten to damage an already vulnerable economy in landlocked Mali, where a brutal jihadist insurgency has raged since 2012.

As Mali's second most important export after gold, cotton is a key source of foreign exchange.

"We're all going to pay the price," said Tiasse Coulibaly, head of a farmers' association in southwestern Mali.

Every Malian worker is potentially affected by the sanctions, but cotton growers fear the measures will provoke spiralling problems in the industry.

The first is cash flow. Malian cotton growers sell to a state-controlled firm, the CMDT, which holds a monopoly. The closed borders and financial sanctions could hurt government coffers, affecting the ability to buy cotton.

The CMDT also gins the cotton -- separating the plant's fibre from its seeds -- before exporting it through ports in neighbouring West African countries.

Now the border closures are hurting exports.

Still, many farmers predict they will not feel the full effects of the ECOWAS sanctions until next year, because of how prices are set.