Venomous Risks: Life-Saving Work

Imagine the excruciating pain of being stung by a tiny Irukandji jellyfish - a feeling akin to an elephant sitting on your chest, leaving you gasping for air and wishing for death. While unlikely to kill, toxicologist Jamie Seymour of James Cook University has experienced this 11 times in his risky job of milking venoms from deadly sea creatures to create life-saving antivenoms.

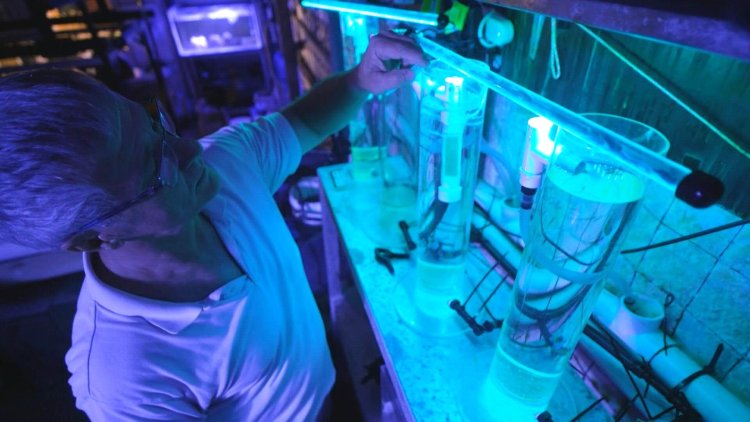

In metal sheds, Seymour's team studies Australia's deadliest marine animals, including the Irukandji, box jellyfish which can kill within 10 minutes, and the venomous stonefish. Despite its powerful venom capable of causing blackened, dying flesh, no stonefish fatalities have been recorded in Australia.

"Australia is without a doubt the most venomous continent in the world," Seymour states, adding that while animal envenomations occur, deaths are relatively rare compared to other causes like vehicle accidents.

Seymour's facility is the only one extracting venom from these creatures to produce antivenoms. The process involves carefully removing tentacles, extracting venom from glands, and injecting small amounts into animals like horses to produce antibodies that are then purified into antivenoms.

Climate change is increasing sting risks, with warming oceans extending jellyfish seasons and pushing them further south. Temperature changes can also alter venom toxicity, challenging antivenom effectiveness. Research into potential medical uses of venoms, like curing rheumatoid arthritis in mice, remains underfunded.

"When you think of the venom, think of it like a vegetable stew. There's a whole heap of different components that are in there," Seymour explains, emphasizing the ongoing work to understand these complex, deadly, yet potentially life-saving, venoms.